Protein structure and translation

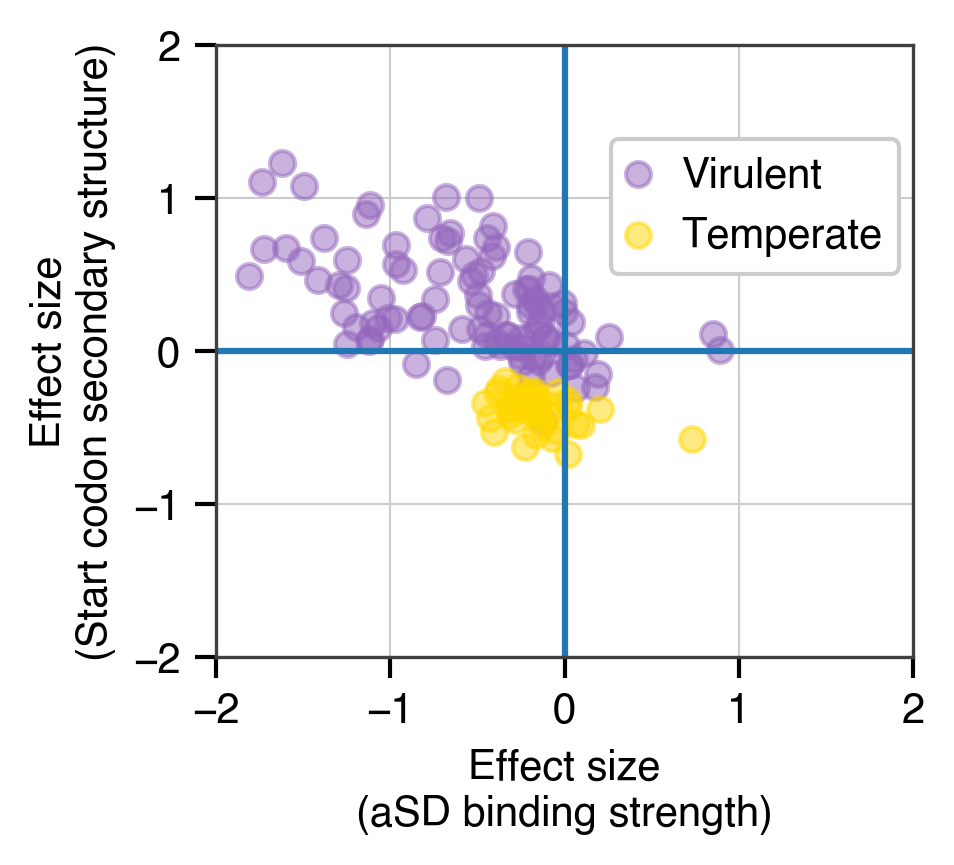

Beginning with my graduate school work, and continuing on through my post-doctoral studies I have focused on characterizing the language of microbial genomes. In particular, my research has looked at how codon usage biases (akin to synonyms in spoken language) and usage of the Shine-Dalgarno sequence (a form of punctuation mark that often defines the beginning of genes) vary within and between the genomes of bacteria and viruses. Perhaps most importantly, my work has looked at what these features can tell us about the life-history of individual species and how they can be leveraged to engineer genomes for synthetic biology applications.

Applications of machine and deep learning to biology

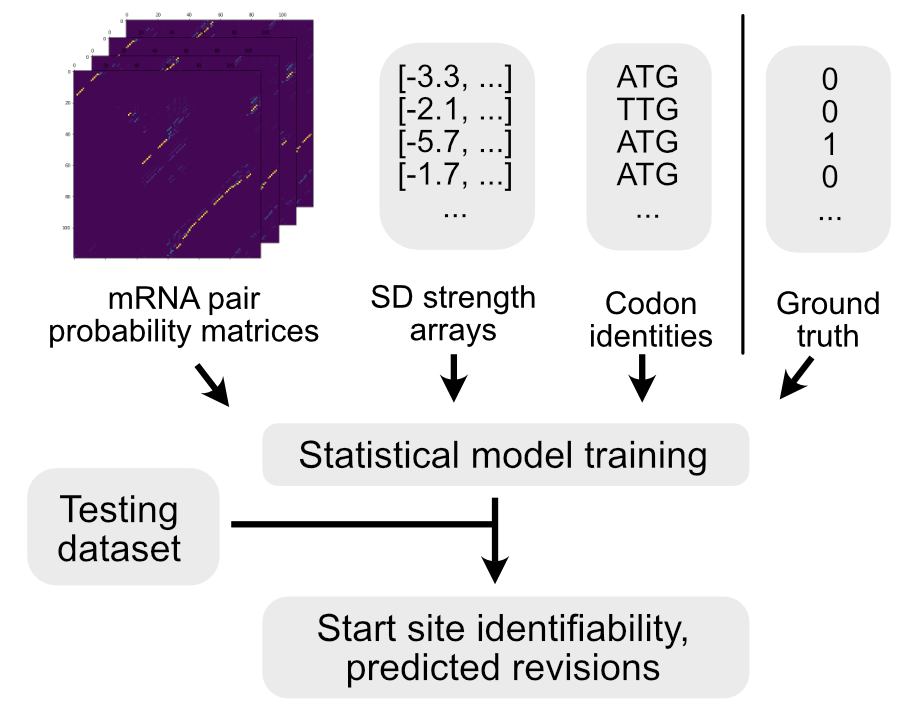

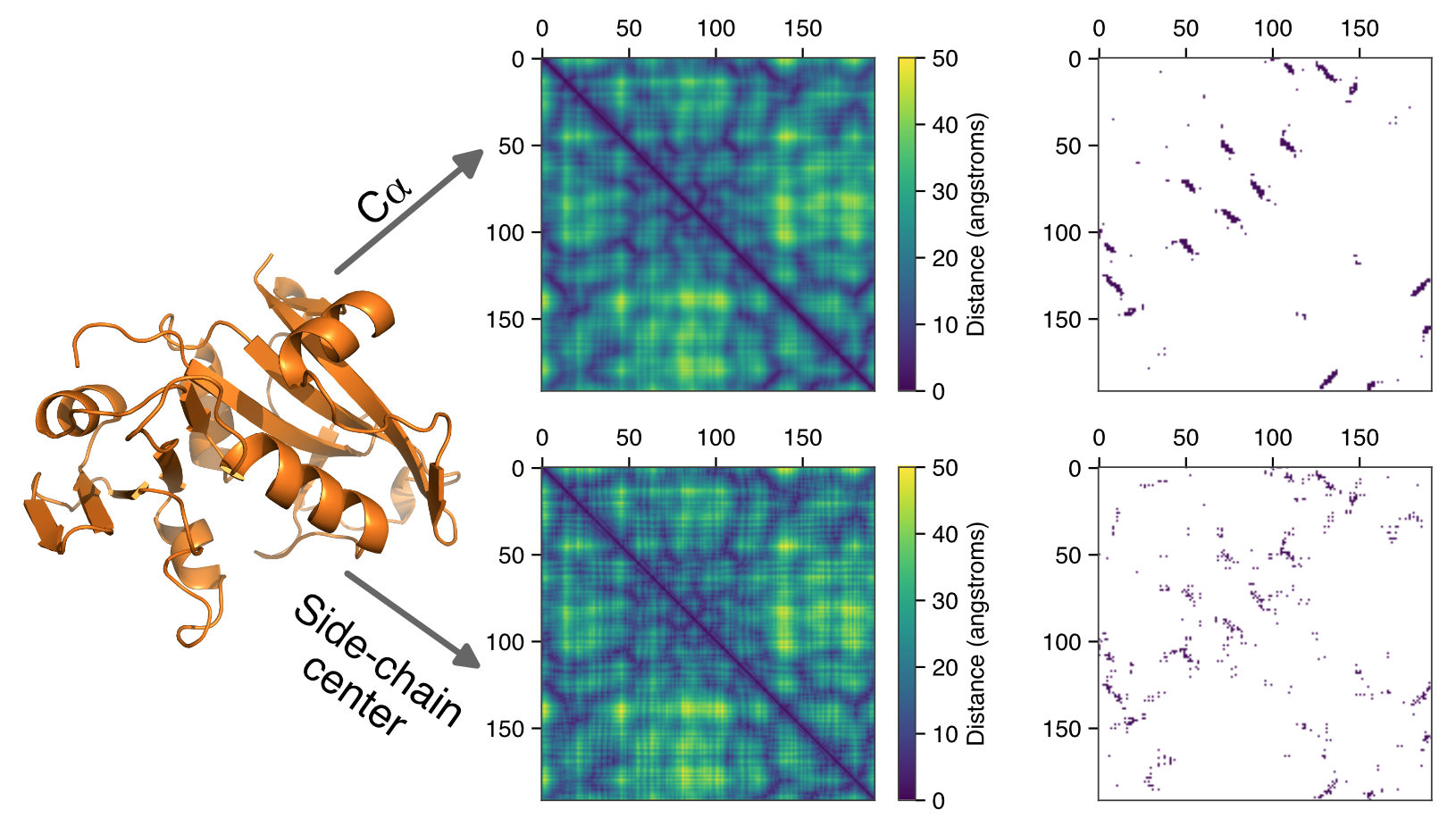

Deep neural networks have revolutionized numerous fields in recent years, but biological applications of these approaches are still in their infancy. Two of the dominant methods that have spurred these advances are Convolutional Neural Networks (particularly for image data) and Recurrent Neural Networks (for text-based data). Microbial genomes can be defined by a string of letters, but the molecules that these letters ultimately create are well-described by pairing-matrices. Both CNN and RNN-based networks therefore have tremendous potential for annotating genomes, and transformer architectures may provide still further advances in this area. My research is focused on how to best apply these tools and to exploit the dominant architectures to make biological advances. In particular, biological data is governed by known physical limits that place constraints on gene predictions but this physical knowledge can be codified and harnessed by deep learning approaches to drastically improve our ability to annotate genomes de novo.

Biological data science

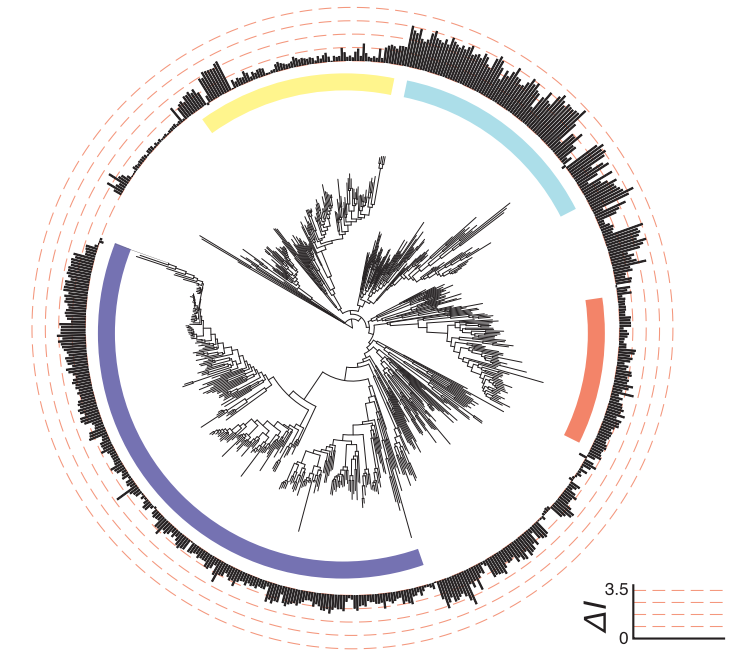

One of the most exciting aspects of being a data scientist working in biology is trying to discern how phylogenetic structure inhibits our ability to make statistical inference, and ideally how to overcome this obstacle. Two siblings are more closely related to one-another than any two random humans, two humans are more closely related to one-another than either is to chimpanzees, and a human and a chimp are much more closely related to one-another than either is to a sea anemone. This lack of independence in data points presents tremendous obstacles to statistical inference, as nearly all off-the-shelf statistical models make the iid assumption (independent and identically distributed). Further, sampling of individuals and species is far-from uniform. We know the genome sequence of more sars-cov-2 viruses than all other viruses combined. Working through these challenges and developing statistical tests and frameworks to account for this feature is an active and on-going area of my research, particularly as it pertains to machine and deep learning models.

The importance of why

While my research has taken a variety of different directions over my career, the common thread that unites these disparate topics is a drive to uncover why?. Data by itself can only tell part of a story, but contextualizing that data within what is currently known and speculating what might come next are critical to scientific advancement. Further, putting these thoughts into general and accessible language for the public to be able to easily digest is critical for encouraging diverse voices to carry on the torch to the next set of interesting questions. Throughout my career I have prioritized scientific communication through written works and oral presentations, as well as mentorship of the next generation of curious scientists.